Forbidden websites

Sick dad, prom dates, and lost keys

Lower the volume

An online commonplace book

This collection of King-Cat comics is a time machine. Not a whirling pod that splits atoms and breaks open new dimensions, but instead a glimpse of John Porcellino’s life in the early 2000s.

As I read each page over and over, I found myself playing this game. I call it: Where was I when?

Here’s how it goes. At the bottom of a comic it may read MARCH 2005.

From there I light a swisher sweet, jog with my memory, imagine, and ask the question, where was I in March 2005?

Was I failing college algebra again?

Was Episode One still the dopest movie ever?

What were my go-to pair of Nikes?

It’s a fun game. Try it at home. But it does make me wish I kept record of those days. A journal, a heart and key locked diary, or, then it’s it heyday, a blog.

We can’t change the past, but we can revisit it. Even if it’s a bit blurry.

Buy your very own time machine here!

Words from lovers. Words

with friends. Instagram Stories

we tell ourselves.

Eyes of the World winked at me from the top shelf.

On the cover, Robert Capa was rockin’ a knit tie, Gerda a beret. I didn’t know who they were, but I knew they were special. I turned to chapter one and gave the first sentence a read:

As Robert Capa tells it: A metal ramp cranks open and lands with a splashing thud. Chilly dawn fog rushes into the craft where thirty soldiers sit shivering, crouched on benches. The floor sways, slick with vomit; the seas have been rough.

Reading that first sentence I realized, pictures of D-Day are so ubiquitous I never asked the question: Who took those photographs?

It’s easy to forget that amongst the soldiers, bullets, and death, were photographers like Robert Capa on the ground. Pioneers documenting war in a brave new way.

Before reading Eyes of the World: Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and the Invention of Modern Photojournalism, I’d never had an interest in photojournalism or photography. Photography was my fathers thing. Not mine.

I’d never read about Robert or Gerda in a text book. Or heard their names in a history lecture. No mention of them in photography class. Hell, Amazon didn’t even list the book in my recommendations.

But Gerda’s story is irresistible, as Marc Aronson and Marina Budhos‘ book proves. The story is a mix of art, love, and living for something beyond yourself. Of stepping forward even when all is unknown. Gerda and Robert’s photography helped usher in a new form of journalism – photojournalism.

But before she became a pioneer, Gerda, then named Gerta Pohorylle, was a Jewish refugee struggling to adapt to life in Paris. Managing the demands of a starting a career. Navigating falling in love. And resisting the rise of fascism in Europe at that time.

As Marc Aronson and Marina Budhos write of Gerda’s early time in Paris:

For a brief while, she and Ruth roomed with Fred Stein and his wife, Liselotte, who had an enormous apartment with extra bedrooms. Fred had originally studied to be a lawyer in Berlin, but when he was unable to practice under Nazi law, he too picked up a camera and was making a go of it professionally.

What good parties they all had there – putting colored bulbs in the lamps, dancing! Fred snapped pictures of Gerta, mugging away. Yes, being poor, a stranger in a strange city, was awful, but to have the solace of friends, all in the same situation, made it easier. Maybe that’s why, as Ruth put it, “we were all of the Left.” That is, they belonged to a loose collection of groups opposed to fascism and in favor of workers’ rights.

Gerta was never exactly a joiner. Her sympathies, her ideas, came from her years in Leipzig. She hated the Nazis and knew how dangerous it was becoming for her family. But she wasn’t one of those who debated every political point. She wasn’t part of the Communist Party, which took its direction from the Soviet Union. But she did care about social issues, about the future ahead. They all did.

For now, there was food and coffee at the Café du Dôme and talk with friends. And photographs. Above all, photographs.

Eyes of the World is an underrated gem. A historic and important book that belongs on the shelf of every historian, photographer, professor, and curious and wonderful soul out there.

Soft navy linens,

stuffed with goose down, hug my skull.

Eyelids flutter, shut.

We lived side by side

Shared walls and parking spaces

Armenia called

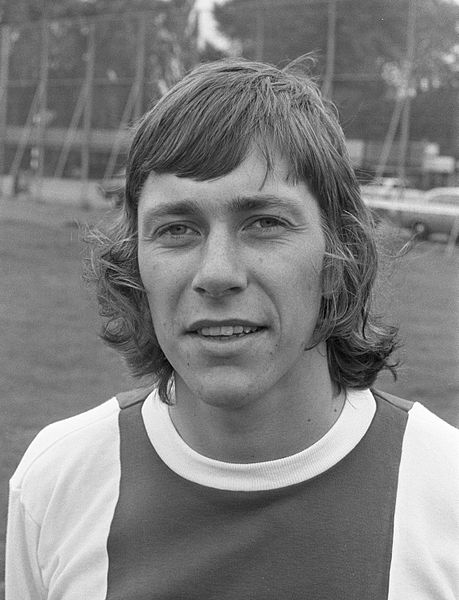

The Muhrens – like all the Dutch greats of their era – learned their football in the streets. Arnold: ‘My brother played with his friends, and when I was five or six I started joining in. I started off in goal but I could never stay there; I was always running all over the place and eventually they said I could play with them. We weren’t exceptional. Everybody could play football at a very high level. At the time there was little else to do but play football. If you couldn’t play football, bad luck: you had to go in goal. We played everyday. If it was raining, we played in the bedroom. At school we played football between lessons. When school finished, we played on the street again; there was no traffic. We played with anything as long as it was round – rolled-up papers tied with string, anything. Some people’s parents had money and could get hold of a proper ball, but mostly it was tennis balls. You develop great technique like that. The ground was so hard, so you didn’t want to fall because it hurt; so you have good balance. And the game was very quick because the hard ground makes the game quicker. No one ever told us how to play. It was all natural.

Arnold Muhren as quoted in David Winners book: Brilliant Orange.

The street football environment Muhren describes, reminds me of the pick-up basketball games of my childhood.

We’d play all day long in the summers, adapting the standard game of full court 5 on 5, into various micro-games.

If there was three of us, we’d play 21. An every man/woman for themselves, winner takes all mini tournament. The goal being to score 21 points, without going over, through a combination of three pointers, two pointers and free throws.

It’s basketball blackjack.

If there was only two of us we’d play HORSE.

HORSE is a shot matching game. The first player calls his shot and the opponent has to match it exactly – off the backboard, nothing but net, left hand only, etc.

If your opponent misses the shot you call, they receive a letter. The first player to receive enough letters to spell out HORSE is the loser.

And if we got bored of all of that…we’d lower the hoop to 6 feet and have a dunk contest.

Not sure it made us better players, but it was fun as hell.

Hand painted signs needn’t always be majestic, 8-bit thunderbirds.

They can be six, bold, black letters adorning a concrete wall.

As the art critic Jerry Saltz says:

But for almost its entire history, art has been a verb, something that does things to or for you, that makes things happen.

How to be an Artist 33 Rules to take you from clueless amateur to generational talent (or at least help you live life a little more creatively). Vulture Guides, Nov. 27, 2018, Jerry Saltz

Art can simply exist to do something for you. Like reminding you you’re outside the office.

Morning clouds graze east.

Sweat flows from our temples.

We Labor. We Play.