One learns by thinking about writing, and by talking about writing — but primarily through writing.

Mary Oliver

It’s in the doing, where the learning happens.

Oliver, Mary. A Poetry Handbook. Taiwan, Harcourt Brace & Company, 1994. pp17

An online commonplace book

One learns by thinking about writing, and by talking about writing — but primarily through writing.

Mary Oliver

It’s in the doing, where the learning happens.

Oliver, Mary. A Poetry Handbook. Taiwan, Harcourt Brace & Company, 1994. pp17

Gabriel Garcia Marquez did not merely write of “trees”; he wrote of almond trees — from a generic group noun to something specific. We can say that Mansa Musa was a “very wealthy king”, or we can say that when he went on a pilgrimage to Mecca he left behind so much gold that he ruined the Egyptian economy. The words “very wealthy” are abstract and conceptual; the fact that Mansa Musa was rich enough to give away sufficient money to damage an economy — that is an action, and it is concrete. A handy question, one asked most often by those in the copywriting business, is: “can you visualise it?”

Consider the King James Version of the Bible, compiled by a committee of forty-two translators and published in 1611 under the patronage of King James I. It is probably the most influential single book ever written in English; the King James Bible has shaped the English language itself — how it was spoken and written — for centuries thereafter. And little wonder! Those translators wrote a work of exemplary literary and linguistic clarity, simplicity, dignity, and elegance. They also had a wonderful penchant for using highly specific, marvellously concrete language. Consider this verse, where the Israelites are turning against Moses as they look back fondly on their time in Egypt:

We remember the fish, which we did eat in Egypt freely; the cucumbers, and the melons, and the leeks, and the onions, and the garlick: But now our soul is dried away: there is nothing at all, beside this manna, before our eyes.

What you also need to do is keep working on your judgment. Keep working on your judgment. That means—and this is something you do, but I’m not sure how many writers actually do it as rigorously as they should—that you have to read a lot. There’s no substitute for that. You have to read a lot. You have to read it with a critical mind. When you read a great piece, reverse engineer it. Read it again with that specific eye where you’re looking at the craft.

When you read a piece by someone you like but this particular piece hasn’t worked, do the same thing. Read it with a critical eye. Figure out why didn’t it work this time. What went wrong? Why did it feel off? You have to hone the reader in yourself, which will automatically make your judgment better, which will automatically lift your ability with it because then you’ll have to work that much harder to please the critic in you.

Rajagopalan, Shruti (2023, June 8). The Creator Economy (No. 81) Ideas of India. https://www.discoursemagazine.com/culture-and-society/2023/06/08/ideas-of-india-the-creator-economy/

Creative judgement. For those of us without editors, it’s an essential skill to hone.

Listen to Shruti’s interview with Amit in its entirety below:

I’ve been waiting months for this podcast episode. Tyler Cowen and Lydia Davis did not let me down.

For a writer of her stature, Lydia openly admits she finds very long books hard to approach:

COWEN: Do you think the late Thomas Pynchon became unreadable, that somehow it was just a pile of complexity and it lost all relation to the reader? Or are those, in fact, masterworks that we’re just not up to appreciating?

DAVIS: Since I hesitated to even open the books, I can’t answer you, because I do find — not all long books — but very long, very fat books a little hard to approach, and some of them, I try over and over. If I sense that it’s really a load of verbiage, I really don’t. I fault myself for not having the patience to get through at least one, say, late Pynchon, but I haven’t.

Don’t despair! Lydia Davis also struggled to read Ulysses. It took two cracks and a move to Ireland for her to finish:

I had a problem a long time ago trying to read Ulysses by Joyce, and started it twice, and finally read it when I lived in Ireland, which made it much easier because I had his context. That too — I suppose because it had different chapters, each of which approached the ongoing story in a very different way — I found that possible too.

I’m believing more and more, that what great books do, what the internet at it’s brightest light does, is make introductions.

Today’s introduction? The Catalan writer Josep Pla:

There’s a book by a Catalan writer called Josep Pla that’s called The Gray Notebook. That’s very fat, but I keep going back to it and delighting in it, but I’m not reading it all at once. I’m going back to it and just sort of nibbling away at it. It was an amazing project. He took an early, very brief diary of his when he was 21, I think, and it only covered a year and a half. He kept going back to it rather than publishing it. He kept going back to it and expanding it with more memories and more material, and I love that idea. Maybe that’s why I can read it.

Lydia admits the Harry Potter series didn’t captivate her. She preferred the writing in Philip Pullman’s The Dark Materials trilogy. But she understands, Harry Potter’s greatest value is hooking kids on reading:

COWEN: How would you articulate why you don’t like the Harry Potter novels?

DAVIS: That’s fairly easy, although I should have a page in front of me. It’s always better if you have the page, and you can say, “Look at this sentence, look at that sentence.” At a certain point, my son was reading Harry Potter as kids do and did. I think he was probably 11 or 10 or 11, 12, 9 — I don’t know. Also, the Philip Pullman trilogy, whose name I always forget. I thought it would be a lot of fun to read the Harry Potter books because I knew a lot of grownups were reading them and enjoying them. I thought, “This is great. There are a lot of them.”

But when I tried to read them, I didn’t like the style of writing, and I didn’t like the characters, and I didn’t like anything about them. Whereas, I opened the first Philip Pullman book and read the first page and said, “This is wonderful. The writing here is wonderful.” I really think there’s an ocean of difference. I wouldn’t put down the Harry Potter books because, as we know, they got a lot of kids reading and being enraptured with books. I think that matters more than anything, really — getting kids hooked on reading.

Brilliant and insightful. Do give it a listen or read the transcript in full here.

Pair with Henry Oliver’s Lydia Davis twitter thread.

All quotes are from: On the Move: A Life. By Oliver Sacks

In the final pages, of the final chapter of On the Move, Sacks returns to one of his favorite topics – writing.

Journaling was essential for Sacks. He always kept a notebook close:

I started keeping journals when I was fourteen and at last count had nearly a thousand. They come in all shapes and sizes, from little pocket ones which I carry around with me to enormous tomes. I always keep a notebook by my bedside, for dreams as well as nighttime thoughts, and I try to have one by the swimming pool or the lakeside or the seashore; swimming too is very productive of thoughts which I must write, especially if they present themselves, as they sometimes do, in the form of whole sentences or paragraphs.

On using journals as method for talking to one’s self:

My journals are not written for others, nor do I usually look at them myself, but they are a special, indispensable form of talking to myself.

Sacks strays away from the tortured writer narrative. His attitude towards writing is similar to Ray Bradbury.

It’s a pleasure. It’s a joy. It’s an elixir to the chaos of life.

The act of writing, when it goes well, gives me a pleasure, a joy, unlike any other. It takes me to another place – irrespective of my subject-where I am totally absorbed and oblivious to distracting thoughts, worries, preoccupations, or indeed the passage of time. In those rare, heavenly states of mind, I may write nonstop until I can no longer see the paper. Only then do I realize that evening has come and that I have been writing all day.

And after seventy years writing is still fun!

Over a lifetime, I have written millions of words, but the act of writing seems as fresh, and as much fun, as when I started it nearly seventy years ago.

The entire conversation will expand your mind, but I wanted to capture Adam’s suggestions for being a productive writer:

COWEN: You’ve written an enormous amount. Just this last week you had a major piece come out in the Guardian, one in London Review of Books. Your books are very long. What is your most unusual writing habit?

TOOZE: I’m not sure it’s unusual, but I think it’s the writing habit that many people have who do write a lot. I write every day, basically. I haven’t always found writing easy at all. I’ve been to a lot of therapy of various types to stabilize myself emotionally and psychologically. I still do. It’s very important for me in handling the stresses that arise in writing.

And one of the things I realized in the course of that is that, actually, rather than thinking it was something terrifying that I had to steel myself to do, the best way to think about it was as something I do every day, so it’s like exercise. If I have the chance, I like to exercise. It’s a puzzling activity. I just treat it almost as a game, rearranging the words, trying to fix things.

I’ll say to all of my grad students, you can do that for 10 minutes every single day, regardless of what else is going on in your life. You can always find that 10-minute slot. So that is the thing that I make sure I do. And that means even big projects slowly move along because then, when you get the big slice of time, the three or four hours at the weekend or something, it’s actually top of stack. You know where to go because you’ve been puzzling away at it and chewing on it every day, even if it’s only for 10 minutes.

COWEN: I give the exact same answer, by the way.

Not ground breaking advice by any means. But it applies well, specifically to editing.

10 minutes of edits a day and eventually you’ll have a finished piece.

Also, Adam’s suggestion for the best way to travel through Germany:

I would say travel. Get on the train. Unless you’re a car nut, and you want to experience the freedom of driving a Porsche at 200 miles an hour, which you can do if you do it at 2:00 am. The roads are clean enough, and they’re smooth enough.

But other than that, ride the train. Sit in an ICE going at, absolutely no kidding, 200 miles an hour, powered by solar power, and watch your coffee not even vibrate. It’s absolutely stunning. They have to put speedometers into the trains to make people aware of how fast they’re going.

Enjoyable. Watch in its entirety here:

Toor: How did you learn to write?

Paglia: Like a medieval monk, I laboriously copied out passages that I admired from books and articles — I filled notebooks like that in college. And I made word lists to study later. Old-style bound dictionaries contained intricate etymologies that proved crucial to my mastery of English, one of the world’s richest languages.

From: Rachel Toor’s interview with Paglia in The Chronicle of Higher Education

And from her Conversations with Tyler interview:

I feel that the basis of my work is not only the care I take with writing, with my quality controls, my prose, but also my observation. It’s 24/7. I’m always observing. I don’t sit in a university. I never go to conferences. That is a terrible mistake. A conference is like overlaying the same insular ideology on top of it. I am always listening to conversations at the shopping mall.

COWEN: My last question before they get to ask you, but I know there are many people in this audience, or at least some, who are considering some kind of life or career in the world of ideas. If you were to offer them a piece of advice based on your years struggling with the infrastructure, and the number of chairs, and whatever else, what would that be?

PAGLIA: Get a job. Have a job. Again, that’s the real job. Every time you have frustrations with the real job, you say, “This is good.” This is good, because this is reality. This is reality as everybody lives it. This thing of withdrawing from the world to be a writer, I think, is a terrible mistake.

Number one thing is constantly observing. My whole life, I’m constantly jotting things down. Constantly. Just jot, jot, jot, jot. I’ll have an idea. I’m cooking, and I have an idea, “Whoa, whoa.” I have a lot of pieces of paper with tomato sauce on them or whatever. I transfer these to cards or I transfer them to notes.

I’m just constantly open. Everything’s on all the time. I never say, “This is important. This is not important.” That’s why I got into popular culture at a time when popular culture was — .

In fact, there’s absolutely no doubt that at Yale Graduate School, I lost huge credibility with the professors because of my endorsement of not only film but Hollywood. When Hollywood was considered crass entertainment and so on. Now, the media studies came in very strongly after that, although highly theoretical. Not the way I teach media studies.

I also believe in following your own instincts and intuition, like there’s something meaningful here. You don’t know what it is, but you just keep it on the back burner. That’s basically how I work is this, the constant observation. Also, I try to tell my students, they never get the message really, but what I try to say to them is nothing is boring. Nothing is boring. If you’re bored, you’re boring.

Watch the full interview below:

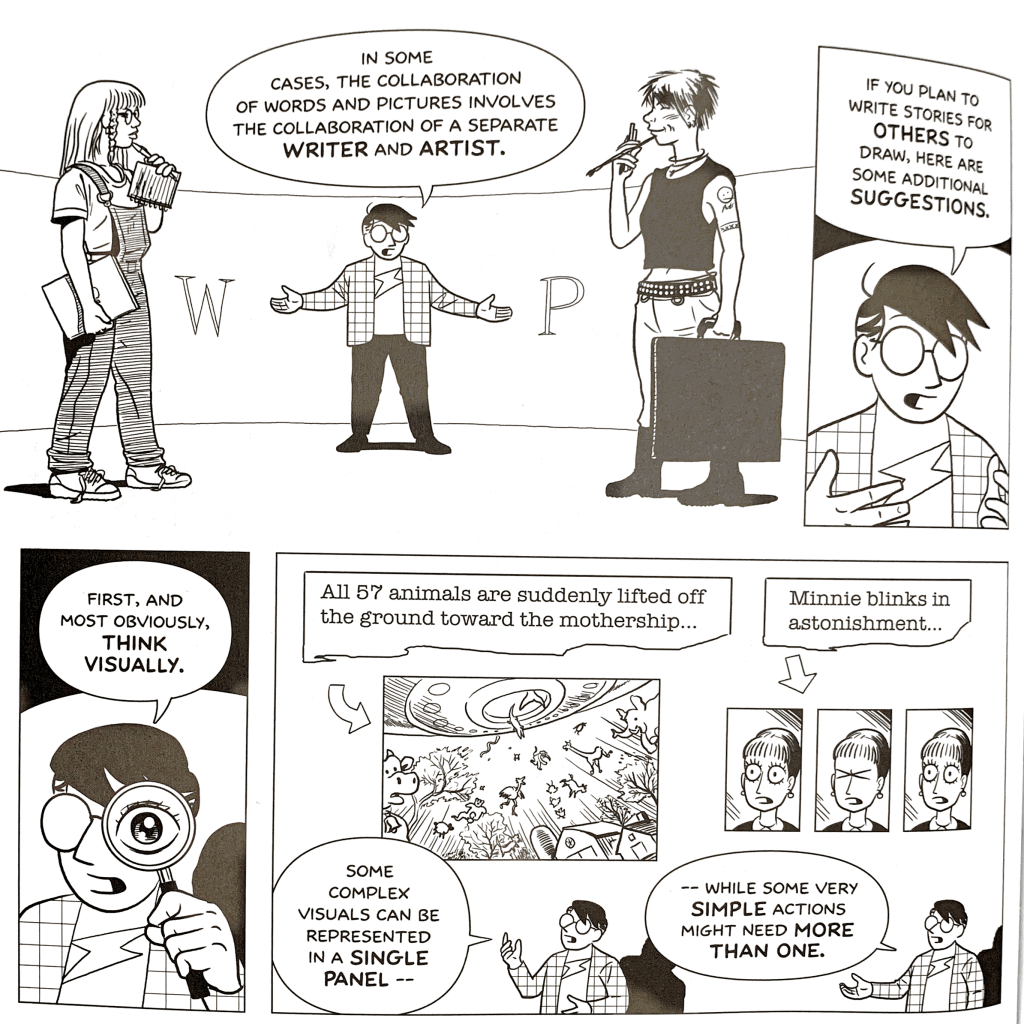

There’s plenty of how-to guides for making comics out there. Still, I can’t think of one as comprehensive as Scott McCloud‘s Making Comics.

Though first published in 2006, Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels holds up. Even chapter 7, The Comics Professional, still shares sage advice to aspiring comic writers and artists alike.

Another Christmas window story. Almost every morning, I eat breakfast in the same diner, and this morning a man was painting the windows with Christmas designs. Snowmen. Snowflakes. Bells. Santa Claus. He stood outside on the sidewalk, painting in the freezing cold, his breath steaming, alternating brushes and rollers with different colors of paint. Inside the diner, the customers and servers watched as he layered red and white and blue paint on the outside of the big windows. Behind him the rain changed to snow, falling sideways in the wind.

The painter’s hair was all different colors of gray, and his face was slack and wrinkled as the empty ass of his jeans. Between colors, he’d stop to drink something out of a paper cup.

Watching him from inside, eating eggs and toast, somebody said it was sad. This customer said the man was probably a failed artist. It was probably whiskey in the cup. He probably had a studio full of failed paintings and now made his living decorating cheesy restaurant and grocery store windows. Just sad, sad, sad.

This painter guy kept putting up the colors. All the white “snow,” first. Then some fields of red and green. Then some black outlines that made the color shapes into Xmas stockings and trees.

A server walked around, pouring coffee for people, and said, “That’s so neat. I wish I could do that…”

And whether we envied or pitied this guy in the cold, he kept painting. Adding details and layers of color. And I’m not sure when it happened, but at some moment he wasn’t there. The pictures themselves were so rich, they filled the windows so well, the colors so bright, that the painter had left. Whether he was a failure or a hero. He’d disappeared, gone off to wherever, and all we were seeing was his work.

For homework, ask your family and friends what you were like as a child. Better yet, ask them what they were like as children. Then, just listen.

Merry Christmas, and thank you for reading my work.

Chuck Palahniuk

From the essay: Stocking Stuffers: 13 Writing Tips From Chuck Palahniuk

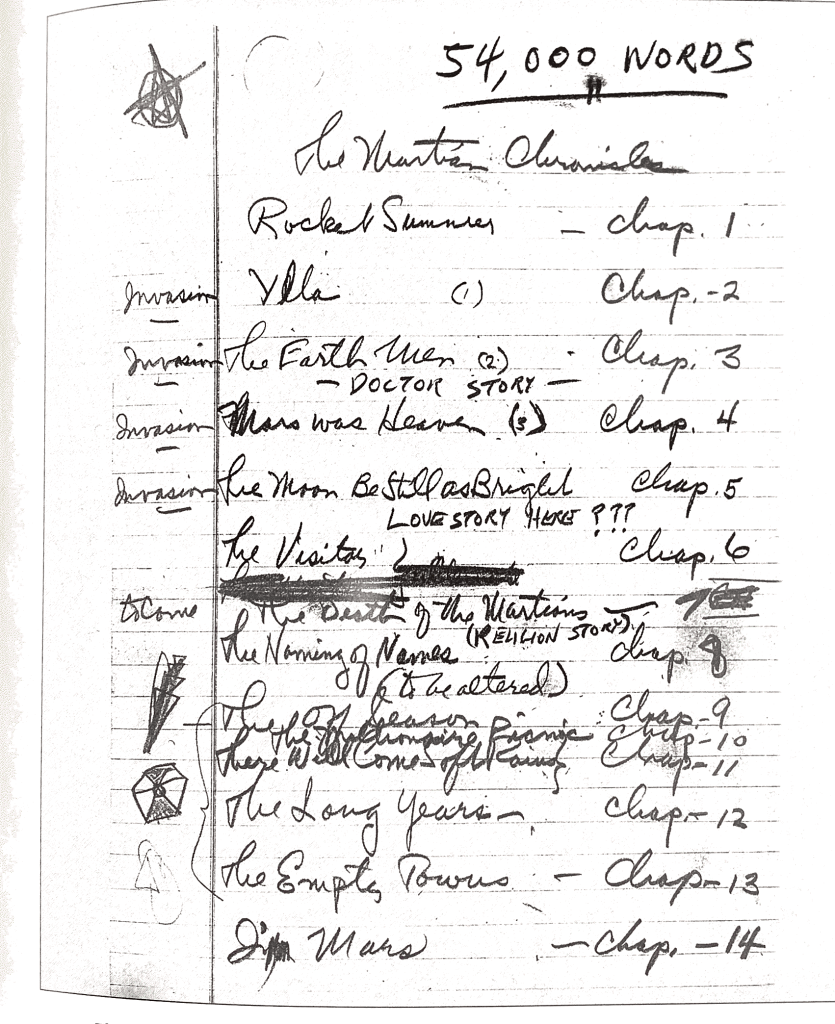

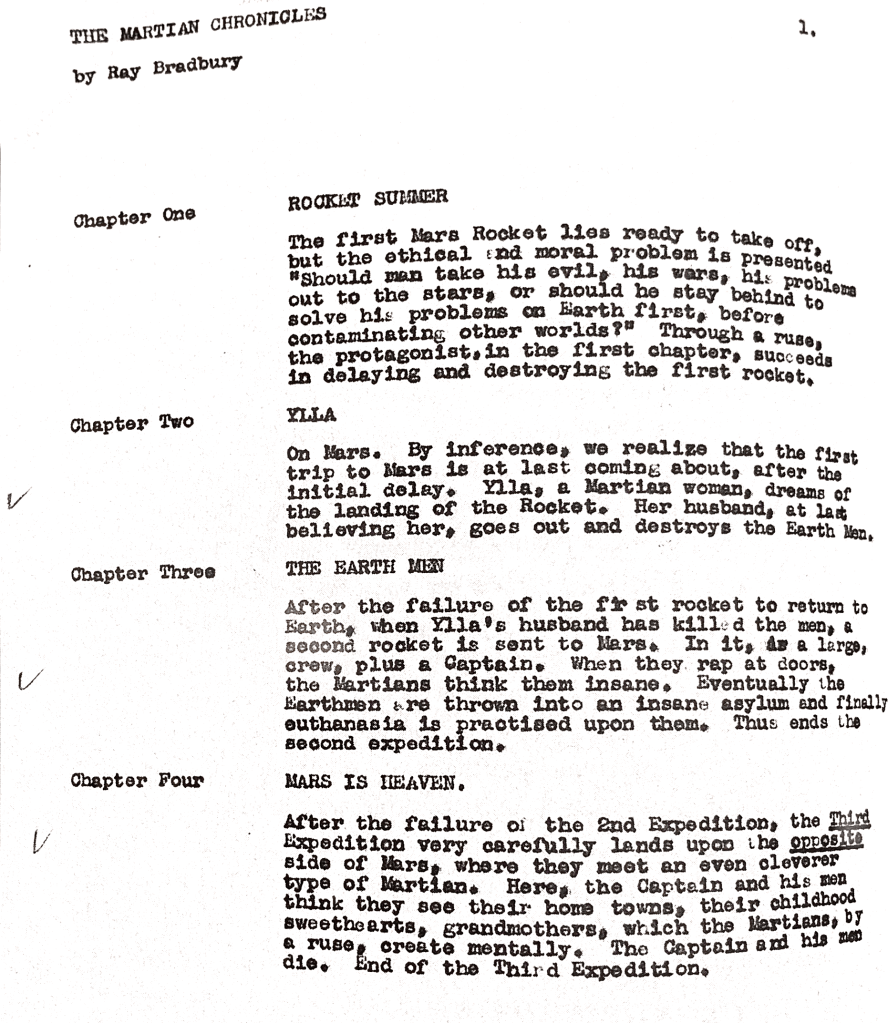

For a writer I associate so much with writing from the subconscious I was surprised to discover Ray Bradbury’s outlines for the Martian Chronicles.

I’m astounded at Jonathan R. Eller and William F. Touponce’s dedication to the research and cataloging of Ray Bradbury’s fiction writing career.

But it’s like Mr. Bradbury says:

Everything I do is a work of love. If it weren’t, I wouldn’t do it. I would like for people to say of me, ‘Bradbury’s books are all his children. Go to the library and meet his family.’

We’re fortunate they did.

From: Ray Bradbury the Life of Fiction. Jonathan R. Eller, William F. Touponce. The Kent State University Press.