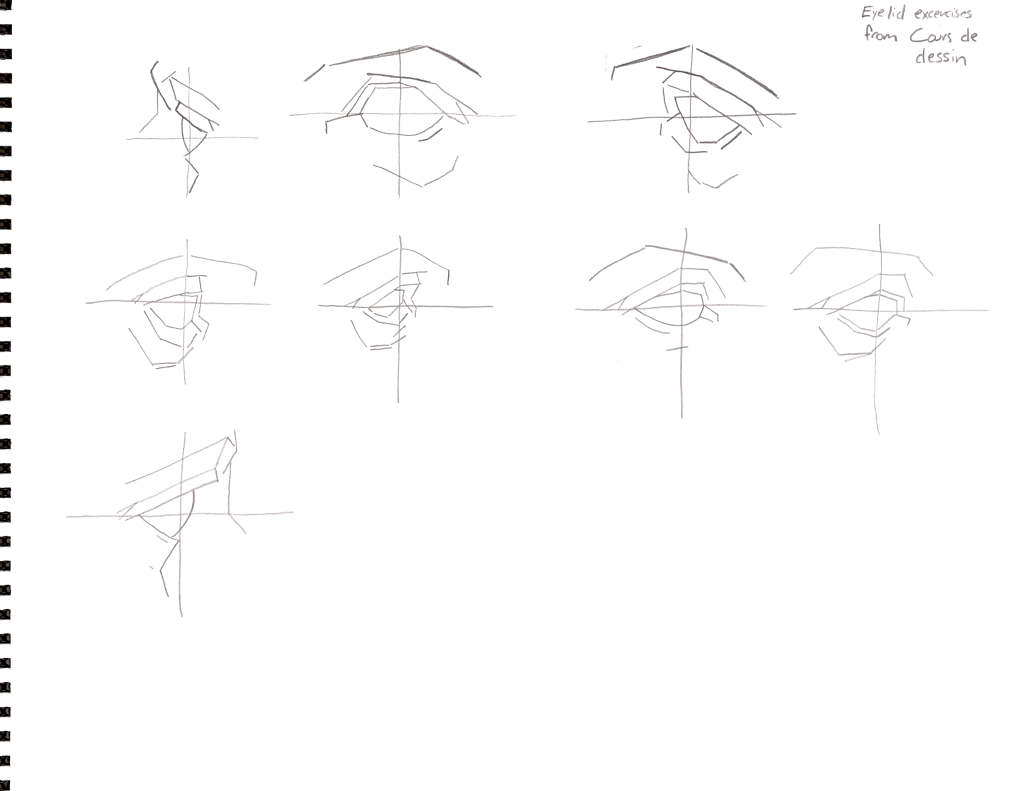

Inspired by a Van Gogh Museum tweet, I picked up this Cours de dessin book and took off.

I mean, if it worked for Van Gogh…

I’m amazed how a few curved and diagonal lines can render such an intricate part of the human face.

An online commonplace book

Inspired by a Van Gogh Museum tweet, I picked up this Cours de dessin book and took off.

I mean, if it worked for Van Gogh…

I’m amazed how a few curved and diagonal lines can render such an intricate part of the human face.

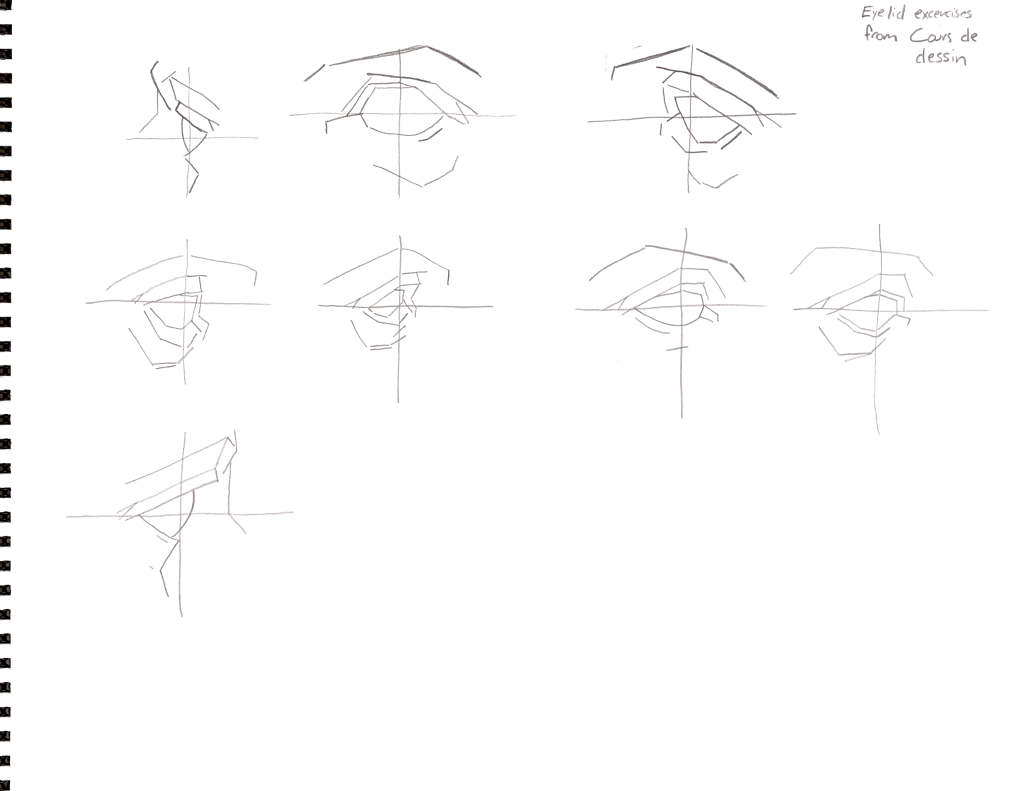

“Roughs” from Jeff Smith’s Bone. Probably the most polished roughs in history.

As a kid, catching a glimpse of a cartoonist’s rough pages provided endless inspiration and encouragement.

My mind melted when I discovered perfect panels didn’t immediately flow from the brushes of master cartoonists.

From: The Art of Bone

By: Jeff Smith

To release some of his jumpy energy and his mind’s ceaseless inventorying and inquisitiveness, Thurber drew. It was as habitual as his smoking. Writing-rewriting, as he often called it- required discipline, focus, research, an amped-up armature of full brain power that included memory, grammar, word and sentence sounds, a dialing in of the humorous of and the heartfelt, the meandering and the meaningful. But drawings? He considered his to be fluid, spontaneous, unhindered, and with rarely a need for erasure, revision, or polish. His daughter Rosemary remembers her father saying that he could even whistle while he drew.

A Mile and a Half of Lines: The Art of James Thurber, by Michael J. Rosen

If you’re looking for some artistic inspiration, or need to smile, pick up A Mile and a Half of Lines. After skimming through five or ten pages you’ll be feening to pick up a pencil and draw.

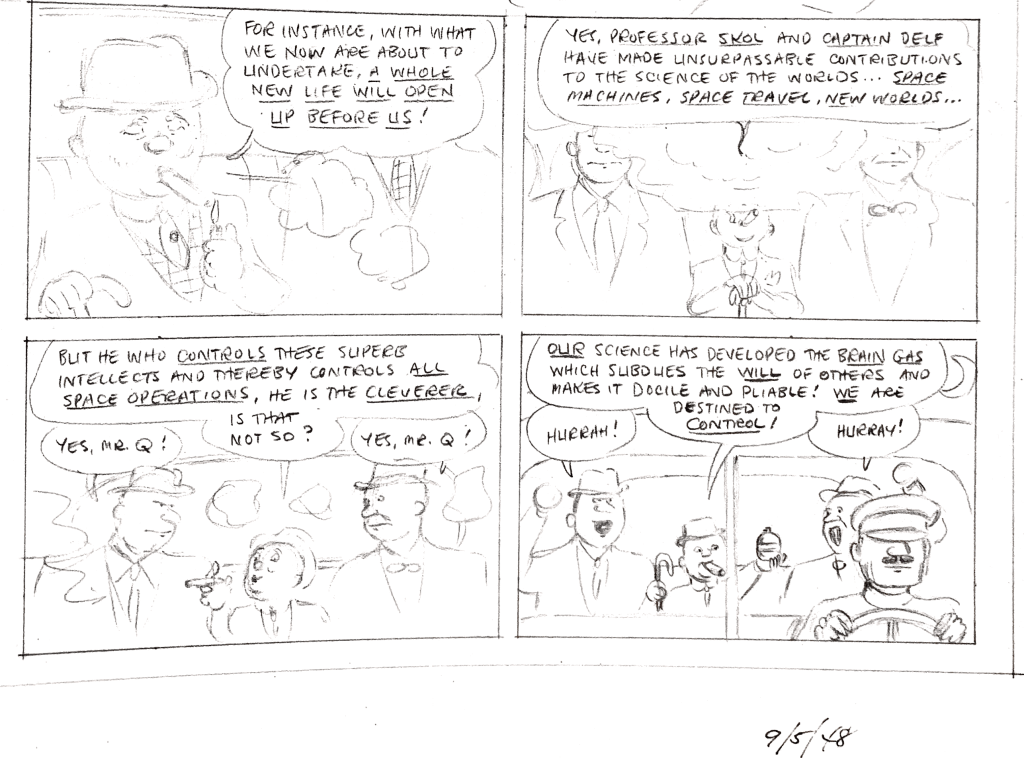

A Four Panel Friday first – layouts instead of completed work. This from an unpublished Spirit story titled: The Cigar.

Important note – Klaus Nordling drew these layouts, not Will Eisner.

Good example of solid panel framing here. Nordling goes from a relative close up of Mr. Q, to framing him between the two henchman. Sweet stache’ on the driver too.

From: Will Eisner: Champion of the Graphic Novel

By: Paul Levitz

Toor: How did you learn to write?

Paglia: Like a medieval monk, I laboriously copied out passages that I admired from books and articles — I filled notebooks like that in college. And I made word lists to study later. Old-style bound dictionaries contained intricate etymologies that proved crucial to my mastery of English, one of the world’s richest languages.

From: Rachel Toor’s interview with Paglia in The Chronicle of Higher Education

And from her Conversations with Tyler interview:

I feel that the basis of my work is not only the care I take with writing, with my quality controls, my prose, but also my observation. It’s 24/7. I’m always observing. I don’t sit in a university. I never go to conferences. That is a terrible mistake. A conference is like overlaying the same insular ideology on top of it. I am always listening to conversations at the shopping mall.

COWEN: My last question before they get to ask you, but I know there are many people in this audience, or at least some, who are considering some kind of life or career in the world of ideas. If you were to offer them a piece of advice based on your years struggling with the infrastructure, and the number of chairs, and whatever else, what would that be?

PAGLIA: Get a job. Have a job. Again, that’s the real job. Every time you have frustrations with the real job, you say, “This is good.” This is good, because this is reality. This is reality as everybody lives it. This thing of withdrawing from the world to be a writer, I think, is a terrible mistake.

Number one thing is constantly observing. My whole life, I’m constantly jotting things down. Constantly. Just jot, jot, jot, jot. I’ll have an idea. I’m cooking, and I have an idea, “Whoa, whoa.” I have a lot of pieces of paper with tomato sauce on them or whatever. I transfer these to cards or I transfer them to notes.

I’m just constantly open. Everything’s on all the time. I never say, “This is important. This is not important.” That’s why I got into popular culture at a time when popular culture was — .

In fact, there’s absolutely no doubt that at Yale Graduate School, I lost huge credibility with the professors because of my endorsement of not only film but Hollywood. When Hollywood was considered crass entertainment and so on. Now, the media studies came in very strongly after that, although highly theoretical. Not the way I teach media studies.

I also believe in following your own instincts and intuition, like there’s something meaningful here. You don’t know what it is, but you just keep it on the back burner. That’s basically how I work is this, the constant observation. Also, I try to tell my students, they never get the message really, but what I try to say to them is nothing is boring. Nothing is boring. If you’re bored, you’re boring.

Watch the full interview below:

The discipline is to wake up in the morning, not turn on the machines you know just um… make some coffee and sit down and just draw whatever comes to your mind

Paul Pope from: The Criterion Channel Studio Visits: Comic Artists on LONE WOLF AND CUB

Who doesn’t love a glimpse into an artist’s sketchbook?

It’s like reading a diary.

It’s like reading a journal.

It’s like reading a MIND.

Noah Van Sciver was open enough to let Frank Santoro and us take a peek.

Have a watch:

And the full interview:

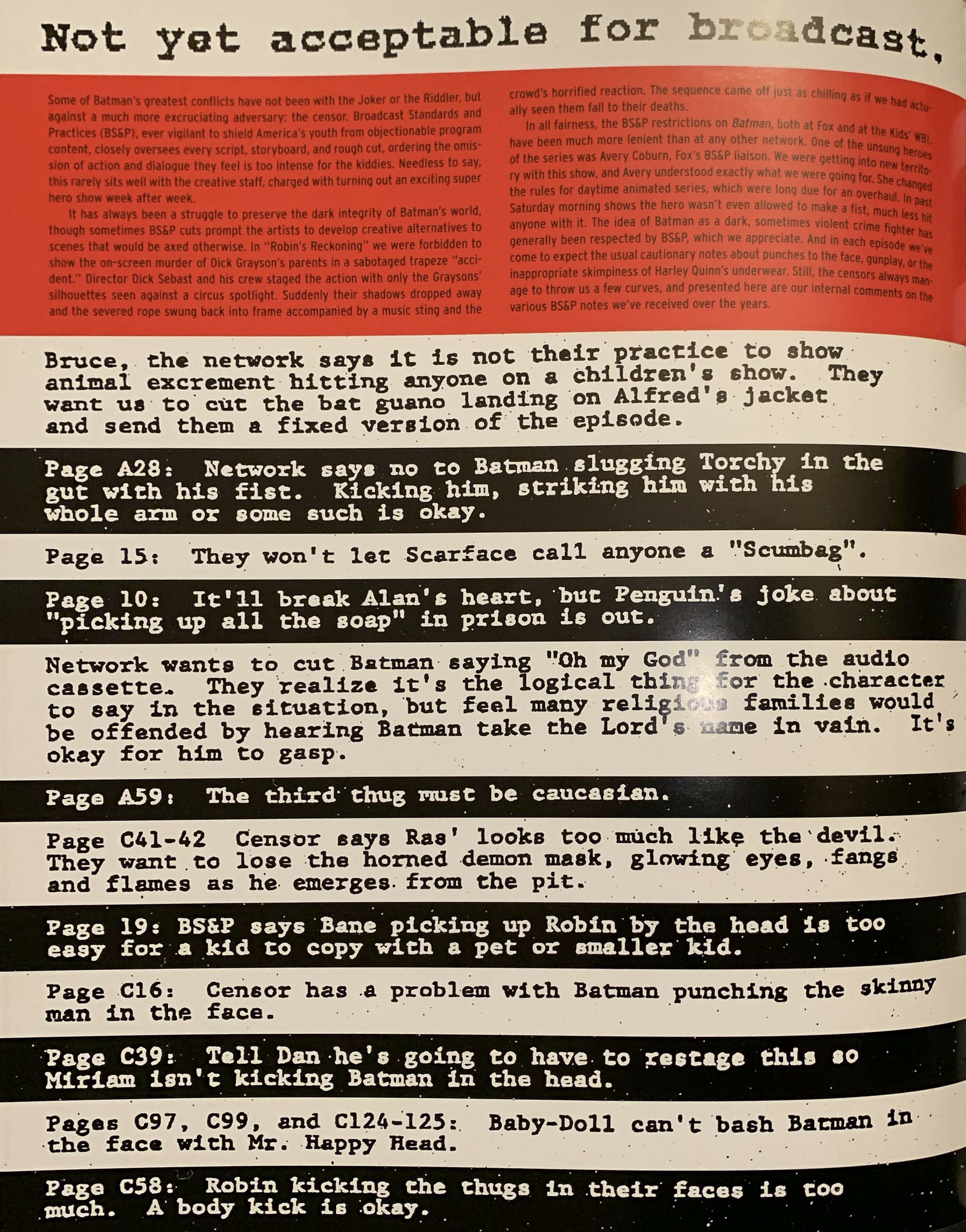

Notes to Bruce Timm from the Broadcast Standards and Practices (BS&P).

How did Batman the Animated Series ever get on the air?

Excerpt from: Batman Animated, by Paul Dini and Chip Kidd.

I’ve written before on how to to write a poem. Followed by how to truly write a poem – study Mary Oliver’s A Poetry Handbook and then practice.

But reading a poem is a whole different pack of monkeys.

I developed this weird method to help me absorb the poems I read. It slows me down, so I don’t rocket through the lines. The aim is to bury the verses in my subconscious.

See if it works for you.

First I read the poem to myself. From the first verse to the last, all the way through.

Then I’ll read the poem from the end to the beginning. I read line by line, from the final verse, back up to the opener:

Reading it backwards is like reverse engineering. It helps me see the poem’s structure. How each verse builds up to the final one.

After that, I’ll read the poem beginning to end again, but this time out loud.

Reading out loud helps you find the poem’s rhythm. I’m sure there’s things like meter and tone involved as well, but I won’t pretend to know how.

Then I’ll read the poem in reverse order again. But this time in full blocks. Starting from the bottom of the poem to the top:

While reading I’ll keep a pencil close. If the poem rhymes I search for the rhyming pattern by underlining all the rhyming words.

Once finished, I’ll log the date, author, and name of the poem in my steno book. Keeping a record gives me a sense of progress.

It’s a practice I stole the from director Steven Soderbergh who publishes a yearly log of what he’s watched, read, and listened to, on his site.

This how I read a poem. You may read a poem once and bin it. And that works too.