Great is today, and beautiful,

It is good to live in this age….there never was any better.

From: Leaves of Grass 150th Anniversary Edition (Penguin Classics), pg.156

No better way to celebrate the last day of October than with Walt Whitman.

An online commonplace book

Great is today, and beautiful,

It is good to live in this age….there never was any better.

From: Leaves of Grass 150th Anniversary Edition (Penguin Classics), pg.156

No better way to celebrate the last day of October than with Walt Whitman.

If you want to see the girl next door, go next door.

Joan Crawford

Good sentences, enviable sentences even, can be found in places other than books or articles. In his book How to Write a Sentence: And How to Read One, author and law professor Stanley Fish shares this story:

One nice thing about sentences that display a skill you can only envy is that they can be found anywhere, even when you’re not looking for them. I was driving home listening to NPR and heard a commentator recount a story about the legendary actress Joan Crawford. It seems that she never left the house without being dressed as if she were going to a premiere or a dinner at Sardi’s. An interviewer asked her why. She replied, “If you want to see the girl next door, go next door.”

How to Write a Sentence: And How to Read One, Stanley Fish. Pg 4

Fish breaks it down:

It is the bang-bang swiftness of the short imperative clause-“go next door”- that does the work by taking the commonplace phrase “the girl next door” literally and reminding us that ” next door” is a real place where one should not expect to find glamour (unless of course one is watching Judy Garland singing “The Boy Next Door” in Meet Me in St. Louis).

How to Write a Sentence: And How to Read One, Stanley Fish. Pg 4

I had to add this to my online common place book:

“Remember this, son, if you forget everything else. A poet is a musician who can’t sing. Words have to find a man’s mind before they can touch his heart, and some men’s minds are woeful small targets. Music touches their hearts directly no matter how small or stubborn the mind of the man who listens.”

The Name of the Wind. Patrick Rothfuss. pg 106

How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading. By Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren.

It’s a book I hesitated to buy. A book on how to read a book? Come on. I got this.

But people far smarter than I recommended it.

Kevin Kelly mentions it on his selections for the Manual for Civilization. Maria Popova has it listed on her Brain Pickings piece – 9 Books on Reading and Writing.

I clicked BUY NOW.

Structurally I thought it would be a step-by-step guide.

Step 1 – Open the book. Step 2 – Don’t use a highlighter. That sort of thing. Instead it’s broken into topics. Essays on how to read specific topics and genres.

Examples include:

How to Read History

How to Read Philosophy

And the chapter I started with: Suggestions for Reading Stories, Plays, and Poems

Adler and Van Doren’s argument for reading quickly surprised me.

The first piece of advice we would like to give you for reading a story is this: Read it quickly and with total immersion. Ideally, a story should be read at one sitting, although this is rarely possible for busy people with long novels. Nevertheless, the ideal should be approximated by compressing the reading of a good story into as short a time as feasible. Otherwise you will forget what happened, the unity of the plot will escape you and you will be lost.

How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading. By: Mortimer J. Adler, Charles Van Doren, pgs 212,213

I’m a slow reader. I’m looking to absorb every character in detail. Adler and Van Doren suggest we’ll remember who’s important:

We should not expect to remember every character; many of them are merely background persons, who are there only to set off the actions of the main characters. However, by the time we have finished War and Peace or any big novel, we know who is important, and we do not forget. Pierre, Andrew, Natasha, Princess Mary, Nicholas- the names are likely to come immediately to memory, although it may have been years since we read Tolstoy’s book.

How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading. By: Mortimer J. Adler, Charles Van Doren, pg 213

They argue this is also true for incidents. We should trust the author to flag what’s important:

We also, despite the plethora of incidents, soon learn what is important. Authors generally give a good deal of help in this respect; they do not want the reader to miss what is essential to the unfolding of the plot, so they flag it in various ways. But our point is that you should not be anxious if all is not clear from the beginning. Actually, it should not be clear then. A story is like life itself; in life, we do not expect to understand events as they occur, at least with total clarity, but looking back on them, we do understand. So the reader of a story, looking back on it after he has finished it, understand the relation of events and the order of actions.

How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading. By: Mortimer J. Adler, Charles Van Doren, pg 213

A book can lose your attention because it’s not clear in the beginning. I fumbled through the first chapter of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, not sure what was happening. I kept on though. It turned out to be one of the best books I’ve ever read.

Adler and Van Doren on the importance of finishing a book:

All of this comes down to the same point: you must finish a story in order to be able to say that you have read it well.

How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading. By: Mortimer J. Adler, Charles Van Doren, pg 213

With that, I’m going to give this reading quicker idea a go. Starting with Patrick Rothfuss‘s Name of the Wind.

I’ll report back.

Keep reading.

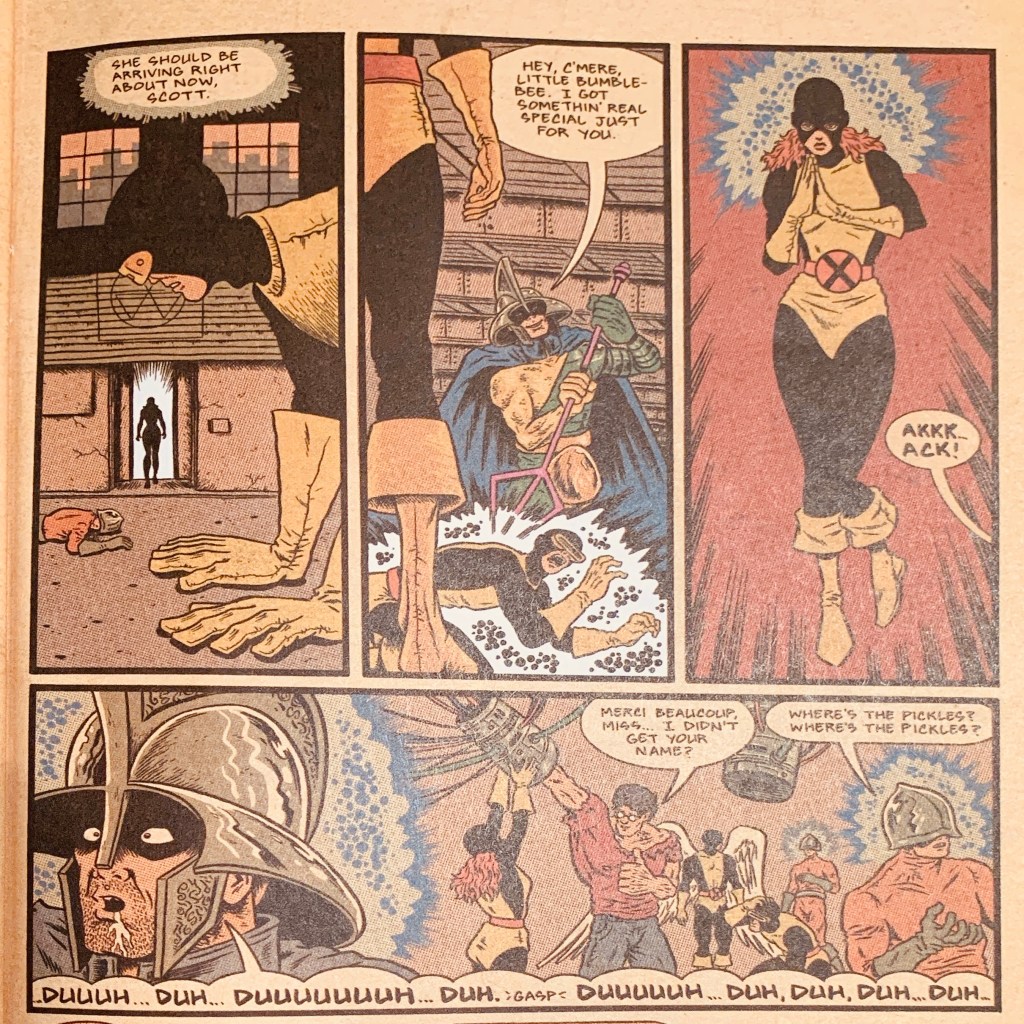

Ed Piskor’s X-Men Grand Design is a tribute to the X-Men’s past.

It’s also a glimpse into the future. A future where cartoonists take on a mainstream project and execute every stage of the the comic making process.

Read on.

Afternoon light ripened the valley

From: Another Life, by Derek Walcott. As read from Teju Cole’s essay Derek Walcott, from his collection of essays – Known and Strange Things.

I read this Derek Walcott line repeatedly. I admit I’d never heard of Walcott before reading Teju Cole’s essay.

With a few words Walcott took me to a mountain range.

I could see the orange and yellows wash across the shrubs. I watched the white and pink light flood over the granite.

I wanted to keep going back there.

I’ve written before on how to to write a poem. Followed by how to truly write a poem – study Mary Oliver’s A Poetry Handbook and then practice.

But reading a poem is a whole different pack of monkeys.

I developed this weird method to help me absorb the poems I read. It slows me down, so I don’t rocket through the lines. The aim is to bury the verses in my subconscious.

See if it works for you.

First I read the poem to myself. From the first verse to the last, all the way through.

Then I’ll read the poem from the end to the beginning. I read line by line, from the final verse, back up to the opener:

Reading it backwards is like reverse engineering. It helps me see the poem’s structure. How each verse builds up to the final one.

After that, I’ll read the poem beginning to end again, but this time out loud.

Reading out loud helps you find the poem’s rhythm. I’m sure there’s things like meter and tone involved as well, but I won’t pretend to know how.

Then I’ll read the poem in reverse order again. But this time in full blocks. Starting from the bottom of the poem to the top:

While reading I’ll keep a pencil close. If the poem rhymes I search for the rhyming pattern by underlining all the rhyming words.

Once finished, I’ll log the date, author, and name of the poem in my steno book. Keeping a record gives me a sense of progress.

It’s a practice I stole the from director Steven Soderbergh who publishes a yearly log of what he’s watched, read, and listened to, on his site.

This how I read a poem. You may read a poem once and bin it. And that works too.

“You are writing, say, about a grizzly bear. No words are forthcoming. For six, seven, ten hours no words have been forthcoming. You are blocked, frustrated, in despair. You are nowhere, and that’s where you’ve been getting. What do you do? You write, ‘Dear Mother.’ And then you tell your mother about the block, the frustration, the ineptitude, the despair. You insist that you are not cut out to do this kind of work. You whine. You whisper. You outline your problem, and you mention that the bear has a fifty-five inch waist and a neck more than thirty inches around but could run nose-to-nose with Secretariat. You say the bear prefers to lie down and rest. The bear rests fourteen hours a day. And you go on like that as long as you can. And then you go back and delete the ‘Dear Mother’ and all the whimpering and whining, and just keep the bear.”

Draft No. 4: John McPhee On the Writing Process, McPhee, John, pg 157,158

A trick to help loosen up your mind and get some words down on the page.

I’m hoping posting it here will help me remember to return to it when all feels impossible.

The prisoner in the photograph is me.

Hole in my life, Jack Gantos

On a sticky August evening two weeks before her due date, Ashima Ganguli stands in the kitchen of a Central Square apartment, combining Rice Krispies and Planters peanuts and chopped red onion in a bowl.

The Namesake, Jhumpa Lahiri

In the land of Ingary, where such things as seven league boots and cloaks of invisibility really exist, it is quite a misfortune to be born the eldest of three.

Howl’s Moving Castle, Diana Wynne Jones

I noticed writing out first sentences is like sliding them under a microscope.

By removing them from their natural habitat – the paragraph they’re resting on, you can see what they’re up too.

See what their hiding.

These three sentences all establish a world. A tone. They all introduce a character and a problem.

Efficient!

Seductive!

Come read more, they beg!

Jack is in prison.

Ashima is pregnant and alone in an apartment that doesn’t feel like home.

And while cloaks of invisibility exist in Ingary, apparently being the oldest of three is a problem.

This makes me think of the first sentences I’ve written.

Did they create the same effect?

The way to learn to draw is by drawing. People who make art must not merely know about it. For an artist, the important thing is not how much he knows, but how much he can do. A scientist may know all about aeronautics without being able to handle an airplane. It is only by flying that he can develop the senses for flying. If I were asked what one thing more than any other would teach a student how to draw, I should answer, ‘Drawing – incessantly, furiously, painstakingly drawing.’

The Natural Way to Draw, Nicolaïdes, Kimon

An artist must have skin in the game.

The work, the practice of drawing everyday, is the path to improvement.